Sometimes the only way forward is forward…and figuring out things the hard way.

I have never wanted to quit a mountain bike ride. But somewhere on the side of Massanutten Mountain in northern Virginia, as the steely spring sky faded to empty black, I was done with my attempt at a full pull of the ‘Ring of Fire.’ Brian Tunstill, my buddy and long-time trail collaborator, lay slumped in a motionless pile beside his Stumpy Evo. "This trail is stupid," Brian said coldly. 'It's just F'n stupid. Why would anyone do this?" According to our devices, we were 40 miles and 9000' of climbing in. We were more than halfway, but by our ragged emotional calculations, it felt like we had walked our bikes more than half of those figures. We were in a dark place, hours behind our expected timeline, clueless of the upcoming terrain, and our forward progress emptied into the night. "This is what we signed up for," I mustered. "A full value experience." But it felt like we were on the verge of failure. Maybe the problem wasn't the mountain or the trail, but what we brought to it.

Brian, 12 years younger than me, and I have been riding together since he was in college at Appalachian State University. Back then, we rambled around with an over-biked crew on the home trails of Wilson Creek, the watershed in Pisgah National Forest that clings to the steep, rain-soaked slopes and highest elevation mountains of the East Coast. The riding here is rooted in a primitive approach to riding. It honors a culture of minimal signs, word-of-mouth maps, and extended hike-a-bikes that prioritize rowdy downhill with improbably bold hucks. These days, YouTube and Trailforks have ended much of that riding style, but the trails are just as good and getting better all the time. We've both raised our kids to ride here and taught them to appreciate both the old style and the new ways.

In the past few years, Brian and I began upping the ante on our riding. We’ve sought longer, improbable single-push rides: Boone, NC to Brevard, NC, via as many trails as possible (150 miles, 32k feet of climbing, 33 hours) and all the trails in Wilson Creek (85 miles, 15k feet of climbing, 22 hours). I wanted to take on a new challenge, something out of my home comfort zone.

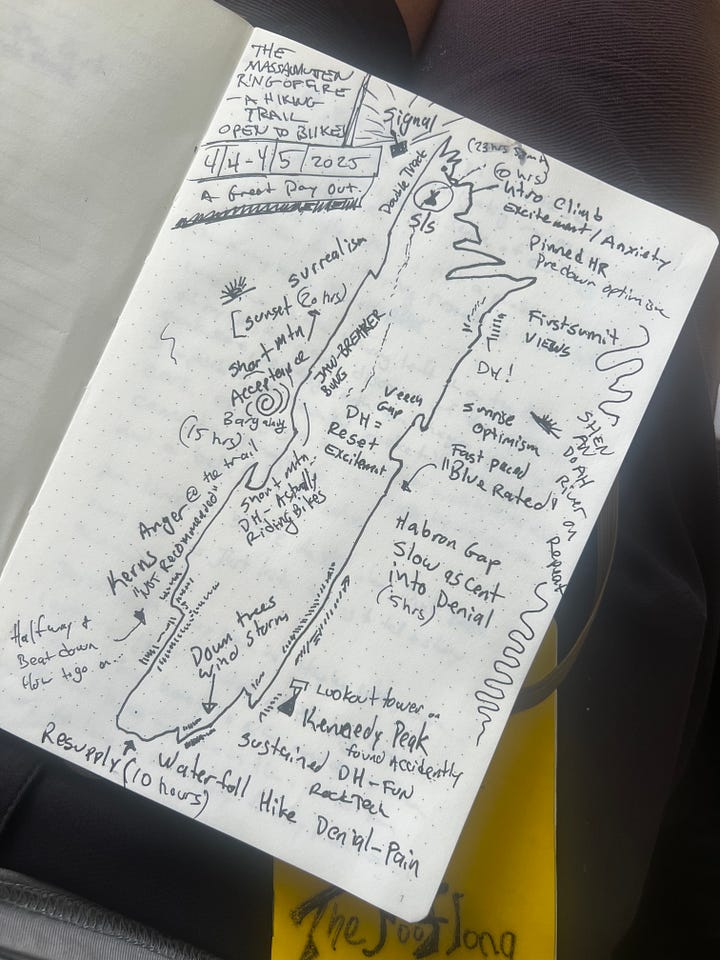

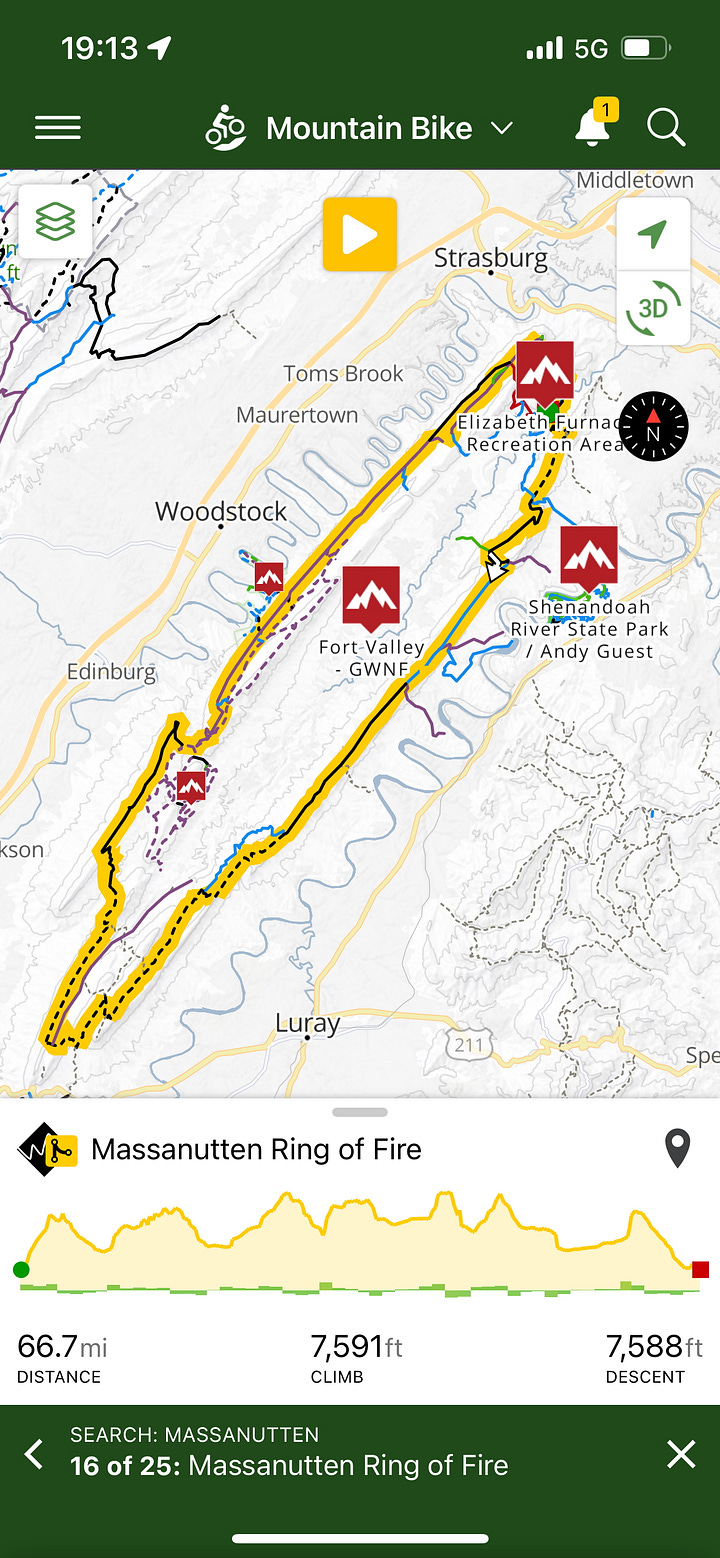

The Massanutten Ring of Fire, a backcountry loop with a mysterious reputation of failed attempts and wild FKTs (Fastest Known Times), seemed like a logical next. Brian was down even when I shared my idea of riding it old school Wilson Creek style – sight unseen, with only minimal research, and on our Pisgah proven bikes - longer travel, heavier bikes, with flat pedals and portly gravity casing tires. After all, Massanutten’s base elevation was 750', and the ridges topped out around 2000.” By Trailforks’ account, the loop is 67 miles with just under 8000’ of climbing, and someone apparently did it in just over 11 hours. How hard could it be? We’re both plenty fit and capable enough for any challenge we’ve yet encountered.

The Massanutten Mountains rise out of the Shenandoah Valley in northern Virginia. Their northernmost extent splits and forms two prominent ridges surrounding Fort Valley. George Washington planned to use the complex and rugged terrain to provide shelter for a potential retreat for his Continental Army in the late 1700s during the Revolutionary War. Washington, known for his strategic foresight, recognized the value of the area's rugged and secluded terrain for military purposes. Terrain that now, a few hundred years later, provides a lot of value for recreation, including mountain biking.

Boulders the size of houses and Volkswagens speckled the ridgetops among hardscrabble, stunted pines. In some places, the rocks tumble ridgetop to valley bottom in vast, complex scree fields. Historic, narrow footpaths enchain the ridges, making a nearly continuous 70-ish mile elongated ring shape. Trail runners first envisioned a full pull of the Ring, a single effort around the loop in under 24 hours. Mountain bikers finally ticked the Ring off in 2012. Since then, a handful of riders typically attempt it each year, some denied and others granted the right of passage. For some time, the FKT, by any means, oscillated between runners and riders. That should have been a warning. A warning we clearly missed.

We'd find out later that the place where our progress ground to a halt was the Jawbone Mountain section - the hardest part of the ride. We had broken down the ride into 11 sections, noting the elevation and potential water sources. My notes showed this particular section spanned five undulating miles. But my hand-drawn map didn’t reveal rocks every single foot of those five miles, protruding up like teeth from a jawbone. The total elevation change here was 1200.' No big deal on paper. Two and a half hours of pedal 10 seconds, hike 30, repeat became the refrain.

"What's wrong with us?" Brian said in disbelief, tinged with an edge of defeat, noticing the blisters on his feet. The downhill hikes were especially physically cruel and psychologically demeaning. We found water where we needed it, but burned time scrounging and filtering. We made wrong turns, following our hopes instead of our instincts. We flailed through what should have been an amazing rip down an iconic trail called Big Run.

On Jawbone, our choices crystallized our movements. Our thoughts were a sodden mix of unpuzzling the rock sequences and disgust with our pace. My blistered feet stung when walking. Brian had worn a hole in his soul. Pedaling yielded little success in the forward movement.

Eyeing the map, we knew a downhill was coming. On our previous big rides, these reinvigorated us, filled our tanks, and stoked the stoke. This one did it too. We vibed down brilliant singletrack, almost like it had been built for bikes, filling our psychological cup as we contemplated the final 20 miles.

Calculating our average speed against the expected mileage, we were looking at at least six more hours on the trail. We were 18 hours in, and it was 10:00 PM. The next leg was about 13 miles, and on Trailforks, it looked like an initial climb followed by a long downhill to the final climb. Brian thought he'd heard that descent was a cruiser. We looked up the average time on Trailforks: 92 minutes. We reckoned it must be a cruiser. We thought it better be, or we'd be seeing the sun rise again…

Bolstered by well-timed text messages of encouragement from friends and family, we soldiered on. After an initial, mostly rideable climb, this next section opened into a fast, flowy, optimism-inducing rip through a couple of miles of open woods. Now we make up time, we thought. After a few minutes, the terrain flattened, and the deja vu of relentless up and down settled in. We thought we were through the hardest part, but this section swirled around us in a journey through the stages of grief. For the next two and a half hours, my skills and senses hastened a full retreat to the center of my own dark valley. At one point, I forgot how to get back on my bike and just fell over. We didn’t talk for what seemed like hours. Each step was a battle against accepting the rocky reality on its own terms.

"How much farther?"

"Five miles."

"It was five miles an hour ago."

"Trailforks is wrong."

"F this trail."

"I'm never doing this again."

For 60 miles, the way we moved forward held us back: We expected things would get easier and that magical high-speed single track would appear. We concluded our bikes were right. We predicted we could intuit the complexities of unknown terrain, aplomb, and unflustered. The clock neared the 24-hour mark, way past our intended time. Our celebration venison burgers lay fallow, still miles away.

"I don't care about time anymore. Let's just get this done so we don't have to come back and do this again," Brian anguished.

Usually, as the end nears on a long ride, a series of bittersweet emotions flood in. On the climb up to Signal, the final climb, a dullness had set in. At the radio tower, we smiled a crooked smile. We'd all but done it. But we had 1 hour to hit the 24-hour mark. Trailfork's average time on the remaining 3 miles was 71 minutes. “How is that possible?” We shook our heads, knowing how far off the mark we were and what we would have to muster to crack the full pull.

Signal’s tumbling screefields dictated a conservative pace, but we hustled where we could, finally breaking through caution and into off-camber rocky flow theory in the last mile. We hit the pavement and pedaled back to our camp minutes before the sky opened up in a springtime storm. The timer stopped at 4:43 AM, 23 hours and 58 minutes after we started. My Garmin showed 74 miles and 14,000’ of climbing.

After some campground sleep and backcountry venison breakfast burgers with a side of homemade cheesecake, we had coffee with a good friend and Harrisonburg local Harlan Price. Recounting our saga, he smiled, "So now you know about high miles and low miles.”

I stirred my coffee. We knew trail miles vs gravel miles.

"So, would you do it again?" Harlan asked.

The easy answer is no.

Harlan nodded and smiled with a look that said, "You'll be back."

Flat pedals and gravity casing tires added to the difficulty of the low miles, but so did the stubborn thinking that this ride would be easier. Resisting reality is the easiest way to suffer. We knew we would suffer on this ride, but thought we'd do it on our terms. But instead, The Ring became a long series of moments of thinking, hoping things would change. The Ring only knows its terms – the scree fields and low mile after low mile. To move forward in the low miles, we finally had to align both the bike and the mind with the forces acting against it and stop expecting anything but the low miles. Low miles were the only way forward.

A person once wrote on a bathroom wall: "Adventures suck when you're having one." What I've always felt was implied in that quote was "...but they make great stories afterwards." Kristian, your adventure sucked. Thanks for sharing your excellent story & pictures. And congrats on completing such a tough ride!

Wow Sounds like a crazy trek. Thank you for sharing your adventure.