Hans Rey And The Spirit of Mountain Biking

37 years of changing lives through bikes and influencing the sport of mountain biking.

If you grew up in the mid-90s in America, you may remember a TV show called Pacific Blue. The police drama, which aired in over 100 countries, featured plenty of stunts, chases, and storylines centered around the police who patrolled the beaches of Santa Monica, CA…by bike. While to some, it may not have stood out from any other police drama of that period, the bikes and riding were at the next level. Much of that was due to the actual professional riders who were a part of the show.

As an 11-12ish-year-old who was excited to ride bikes, for me, watching the show was nothing short of dumping gasoline on a flame of stoke. I was obsessed with riding bikes, and there just so happened to be plenty of fuel for the fire already readily available to me — some of my best friends’ parents owned the bike shop in town, where I could hang out after school at least one day a week. That shop just so happened to be a Trek dealer in the era of the Y-22, and although there wasn’t a single one of those bikes in the store, my buddy Dylan had a VRX-400…that was the next best thing…that and the catalogs I could look at and bikes I could dream of one day riding. Add to that the GT Team Trials bike that my friend Will’s dad had, which I was able to borrow and ride occasionally, the SPIN wheels I found second-hand, and that passion for bikes had the right mix of fuel to burn year after year. Seeing it on mainstream TV was an accelerant for the fire. To young Daniel, it was the coolest thing ever.

Since those formative years, bikes have continued to be a massive part of my life, and that fire has only grown. Thinking back, that show was not insubstantial in fueling my passion for riding bikes. It undoubtedly brought mountain biking into the mainstream for me and countless others. And while few people today would regard the show or its riding as relevant, 25-30 years ago, it was ahead of its time. Hans Rey and the other riders involved were critical in establishing its relevance. While the show itself, the stunts, riding, and culture portrayed were as ’90s as they could be, Hans continues to stay relevant. He has grown even more to become a massive positive influence in the sport of mountain biking and the culture of bikes, helping people around the world.

I recently had the opportunity to catch up with Hans and talk about his story, what fuels his passion for bikes, how the sport of mountain biking has changed from its beginnings, the spirit of mountain biking, and how his charity is helping get people on bikes around the world.

Catching up with Hans ‘No Way’ Rey

Daniel: You've been riding a long, long time, obviously longer than many people. How did you get started riding? What was the catalyst for getting you into the sport?

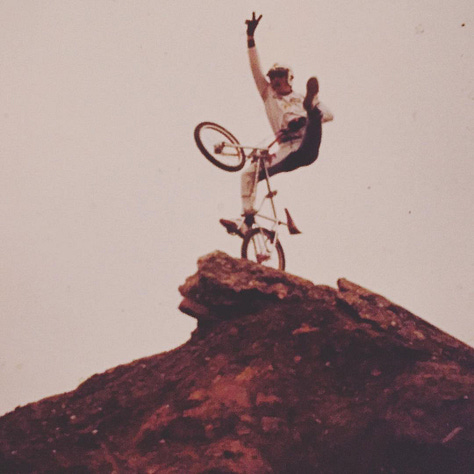

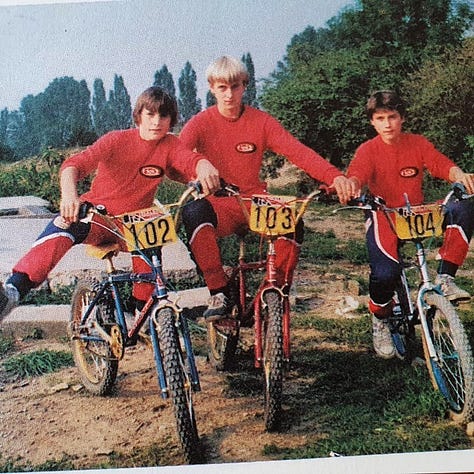

Hans: My background is as a trials rider, and unlike BMX and mountain biking, which are American sports, trials are more of a European sport. I grew up in Europe and lived there until I was 20. The whole trials scene was always in Europe and on 20-inch bikes at the time…this was in the ’80s.

Hans: But one year, this guy came over and told me, “Man, you need to come to America sometimes and show them what real trials riding is because there is a new sport in America, and it's called mountain biking.”

An American trials rider named Kevin Norton would come over and compete with us Europeans. He was also sponsored and even made money. The trials guys in Europe, as much better as they were than any of the Americans, they were all still amateur guys. But one year, this guy came over and told me, “Man, you need to come to America sometimes and show them what real trials riding is because there is a new sport in America, and it's called mountain biking.” And in those early mountain bike races, trials were a big part of it all.

They had stage races where a rider had to do a cross country, a downhill, and a trials competition on the same bike. It was all 26-inch stuff and much more mellow trials than we were doing in Europe. At the time, I was just starting to go to university and I figured this would be a great way to end my biking career — go to university and visit America.

I came over, and the floodgates opened. It was the right time, the right place. I got introduced not only to the whole scene but I found sponsors like GT, who I'm still with after 37 years. I was introduced to the Laguna RADS bike club, one of the oldest mountain bike clubs in the world, and the OG pioneers of freeriding, who I did my very first ever mountain bike ride once I arrived here. And then, I decided to stay in the States maybe for another year or another semester before I would go back. And that got extended year after year, and they're still waiting for me to come back at the university!

Daniel: When you say free riding, I think a lot of people feel like that only started, what, 20 years ago, 15, 20 years ago in Utah with Rampage stuff and on the North Shore and whatnot. But you were at a much more “grassroots, early-on” stage of what freeriding was, right?

Hans: Yeah, I mean, or I called it extreme mountain biking because that was literally five years before the word “freeride” was even coined or adopted from snowboarding. The RADS were known to ride the steepest trails at the time at least, and they would hike and bike and bushwhack and ride stuff…I remember we did a ride one year, and it was a ride that involved also some heavy beer drinking and activities. And we ran into John Tomac and Greg Herbold at the end of the ride. They joined us for the last downhill. And, I mean, those two guys were the two of the biggest names in the sport at the time. At the bottom, I remember saying, wow, this is a new dimension of steep. And we were all so stoked. So we had this reputation of these original “freeriders.” And even in my videos, I did freeride kind of stuff - riding extreme trails and doing some drops. But of course, all that changed when the BC guys put it on the map when it became bigger. And also, at that time, full-suspension bikes became available, and you could actually start hucking stuff, which on a hardtail wasn't that much fun.

But yeah, so it goes way deep. And you know what the cool thing about The RADS is? Because The RADS, very much like the freeride scene now, and also very much like the original clunker guys, they had this original spirit of mountain biking that got a little bit lost in the heydays of the golden era of mountain biking. Because at that time, it became all a bit about racing stopwatches in lycra and that original spirit got lost. And I mean the clunkers really had that same freeride spirit and The RADS had what this new generation of freeriders now do with their backyard jams and with their just “go and ride big mountain stuff.”

Daniel: That’s interesting - it makes me think…How have you seen the spirit of mountain biking, as you describe it, change over the years all the way up to where we are now? I think about my 25+ years of riding bikes and 15 years of working in the bike industry, and I've seen it change quite a bit. We’ve seen an entirely new sport - gravel racing is a thing…It's the fastest-growing segment in the sport now. Some people are very interested in NICA racing, which is super cool. I do sometimes wonder if people get caught up in the mix of feeling like they have to race in order to ride a bike because everyone around them is being competitive…but how have you seen the spirit of mountain biking change? Where do you see it going in the future? What is “The Spirit of Mountain Biking?”

Hans: I mean, the beauty of mountain biking is that it can be interpreted in so many different ways. And that's ultimately what happened. Some guys interpret it with NICA racing, some guys with gravel racing, some guys with North Shore riding, some with dirt jumping, and some with big mountain riding.

Back in the day, if you wanted to be a professional mountain biker, you had to be a racer. There was no other way.

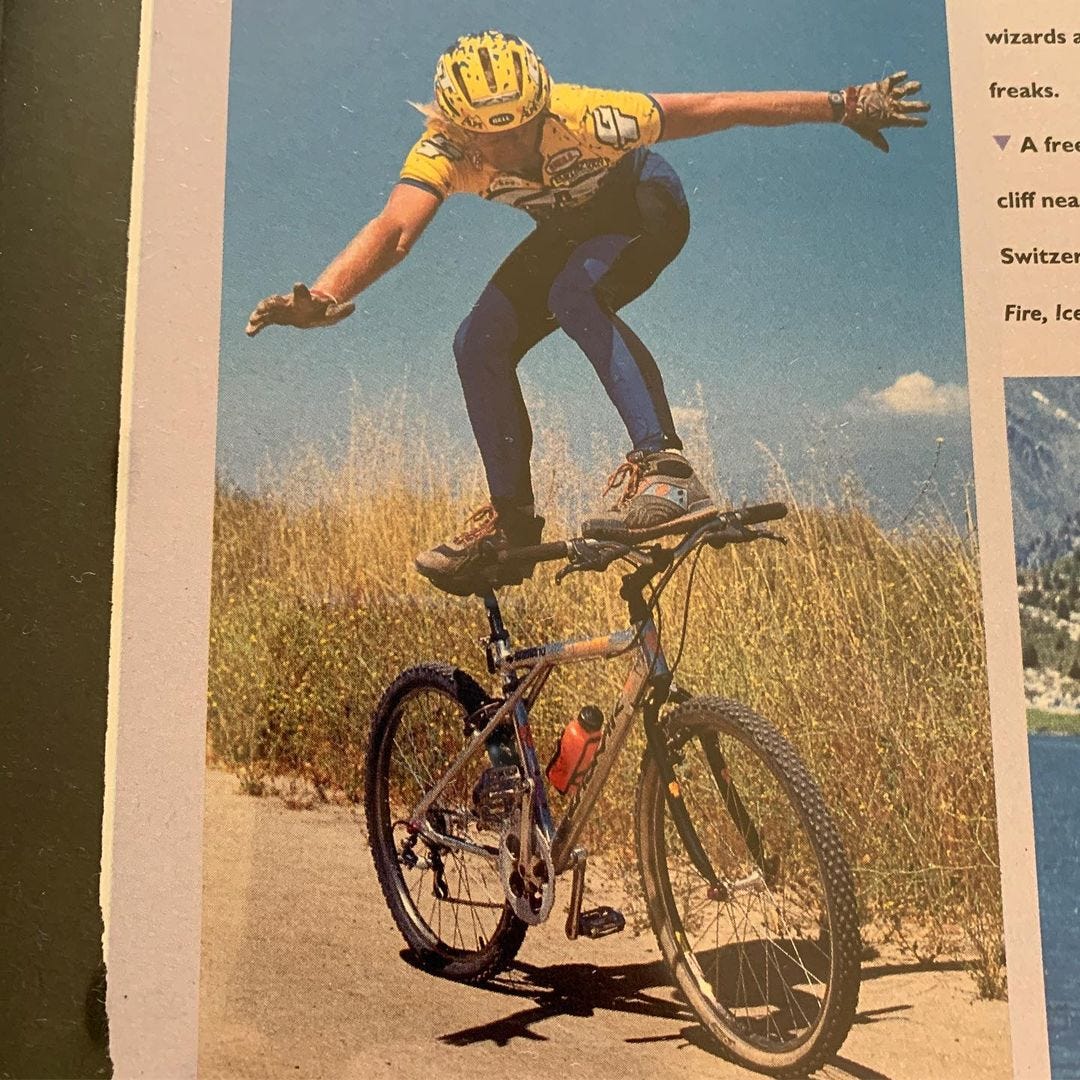

In the old days, there was this one understanding of what mountain biking embodied with the clunkers. That changed very drastically with the era of racing and then the boom (of the bike industry) ultimately. But out of that boom, a lot of subcultures emerged. Along with some of the stuff I've done. Back in the day, if you wanted to be a professional mountain biker, you had to be a racer. There was no other way. And I was one of the first guys who started making a career with nonracing stuff and literally creating content, doing trials shows, doing stories for the magazines, and ultimately, the first action videos.

And Nowadays we have all these little subcultures and I think they all come to the same conclusion when they fulfill their circle in their little subculture: they have the same kind of cool mountain bike stoke, and then a lot of these other subcultures have. So that stoke is still there. It just can be achieved in different ways and with different kinds of attitudes. It’s a common thing that we all have besides the bike, riding in the dirt, and having fun…

Daniel: You were one of the first people to make your career out of not racing. What was that like? What was it like approaching sponsors and trying to make it work? And how have you managed to stay relevant throughout your career? The industry has completely changed. The media landscape has completely changed. We see racers and people riding professionally who can't make it work for three years, much less 37 years. What have you done that's different? How is it continuing to work for you?

Hans: I mean, it's been a ride, and I was influenced by other sports, so sometimes I would look at them and see what's going on. Some other action sports were a few years ahead of mountain biking. I looked at the extreme skiers and I saw how those guys took it from Alpine racing to jumping off cliffs and then doing video segments. And, I would learn from the skate industry or the snowboard industry. I tried to use my trials skills outside of the traditional trials competition. That's why I started going to these waterfalls, volcanoes, and glaciers. Then, all of a sudden, people could relate to it. People also could relate to my trial skills much better once I started riding a regular mountain bike, not a 20-inch special modified trials bike with a skid plate. Once I started doing all my tricks on a mountain bike, people were like, “oh, wow.”

They themselves could barely bunny hop up a curb, and I would ride up a car from the side. The pioneer work wasn't necessarily easy, because at the time everything was about cross country, then downhill second, and then a little bit of slalom stuff. Then the trials guys were the spectator attraction at the venues where people would watch, and they loved it, but nobody would care so much about the results and stuff. It was more like entertainment, and we often felt like the unwanted stepchildren. But out of the trials competition evolved the video scene, show riding, street riding, and all that.

Often, they came from road racing, so they loved the cross country guys, and to explain to them, “Hey, I still want to get paid even if I don't compete anymore.”

So, the pioneer work was really hard to explain to a team manager. Often, they came from road racing, so they loved the cross country guys, and to explain to them, “Hey, I still want to get paid even if I don't compete anymore.” And they were like, “What?” So it took a lot of convincing, but then people started realizing, oh my god, Hans can take the sport to the people. If the people don't come to this remote forest where we are having our competition, Hans can go downtown New York City and do a show at the World Trade Centers a few days before the Hunter Mountain Bike World Cup, for example, and attract huge crowds and TV stations and newspapers who write about it and he can do shop visits where he can not just shake hands, he can actually do some trials tricks and stuff.

And that worked out really well for me. I often say back in those days, there were about five guys who made a living of non-racing and nowadays, we are sharing that same non-racing pie with about 5,000 people all trying to make a living because it's not just the freeriders and the trials guys or the guys who do street riding or shows. There's the influencers and the social media guys. You even have to count the tour guides, and there are hundreds if not thousands of tour guides all over the world. Many of them are kind of co-sponsors, too, and they are at least eating from that marketing guy of getting free bikes or getting some bonuses. So there's a lot more people eating from the pie. Of course, the pie has grown a lot bigger, but back then, it was easy in a way to make yourself a name because there were so few other competition people doing it. That, and we had the stage to ourselves, but at the same time, it was hard to convince people that they should put some of their marketing money towards what we were doing. The same happened later than when freeride became a thing, and there were people like the Fro-riders, and then other companies needed to think, “Wow, do we need to sponsor one of those freeride kids too, or a team? But no, we don't want to take money away from our racing team.” And so that's kind of how it all evolved.

Daniel: That’s all incredibly insightful. So, how do you think, given the current media landscape…how can athletes stay relevant and bring value now? What do you think are some of the most important things to do that?

Hans: Well, partly back to your last question. The one other thing is that I embrace new trends, and that leads to this question in that you sometimes have to embrace new trends. I mean, just like what you guys are doing right now with this new (Substack) platform where you don't know where it's going, but sometimes you guys, in a way, do pioneer work if this thing goes somewhere. And it's the same with so many little mini trends that have come and gone in our industry. Sometimes, you have to kind of be open to new stuff. I think the thing that riders often didn't understand was that for most people who became pros, it was kind of their hobby, their passion, the love of their life to ride bikes. Then, all of a sudden, somebody offered them some money to race or compete because they were good. Sometimes, they kind of didn’t understand that, at the end of the day, it was still the business.

These people didn't just give them money because they were the sugar daddy of the little high school baseball team. They were ultimately a business, and they wanted something in return. And I think the athletes who treated it a bit more like a business are doing better and also have more longevity in our sport. I mean a lot of these older names you still see, hear around and see around, not only did they build themselves a foundation, but they've been working on that continuously and keep putting wood in the fire. And that takes adjustment.

…bikes have gotten better, jumps have gotten much better, safety equipment has gotten better, and how-to videos are available…but ultimately, if you hit the ground, it still hurts the same.

I think nowadays, even more than ever, every generation keeps raising the bar. Once somebody has seen those first videos we did, it was easier for them to emulate what we were doing. Then, the next generation would try to outdo that. They often succeeded, but the bar keeps raising generation by generation. Nowadays, if your dream is to become a downhill racer or a top slopestyle rider, I mean you have to start doing double back flips at 13. That's staggering. So there's a high risk, even though bikes have gotten better, jumps have gotten much better, safety equipment has gotten better, and how-to videos are available…but ultimately, if you hit the ground, it still hurts the same.

Daniel: While we’re on the subject, do you think that the availability of media and the proliferation of just so much how-to content and people seeing everyone doing things in real-time…it's not like people are picking up a magazine and looking at it a month, two months later or watching a race replay or something like that…Do you think that the pace for all that has gotten a lot faster given all of these things and that kids are learning a lot faster? What are your thoughts on that?

Hans: Yeah, it is. It has a snowball effect. It is scary. I'm glad I don't have to make a name for myself in 2024 because, like I said, the bar has been raised so high, and it is kind of crazy. Yeah, what's going to happen? And there might be a way, certain things, when a sport goes too extreme into one situation…Like in freeride, in the early days, it was all about who could go higher and higher and do a bigger drop. But then even those riders were like, yeah, I do that once a year for film segment, but I'm not going to do that every weekend now and prove to people that I can do it. It's really dangerous and scary. And so then people said, let's just do half as high of a drop, but we'll do a no-hander and/or a 360.

And then it became about tricks. But now it has evolved so much in the opposite direction that it's all about tricks. And if you don't have a gymnastics and a BMX background, I don't think you need to go to a slopestyle contest. It's so crazy, and it's kind of taken it so far away from mountain biking in a way. But the bikes are very special bikes, and the sport always evolves, and then sometimes it comes to a stop, and then it evolves into a different direction. And then on top of it, for the people who are in the social media business, there's all these challenges, things are so shortly lived, even the best riders do a video that is really good, and then five days later it's almost forgotten. It's a very short lifespan of these things, and it's, it's just short-lived…

Daniel: So, what is mountain biking now? You touched on that a little bit earlier, but what would you say mountain biking is? What does that even encompass? I guess it's open for interpretation, right?

Hans: Well, that's like asking me what is music all about, right? Now we have jazz and we have blues and we have punk rock and we have classical, and that's what it is. And it's not “music” anymore. It's like mountain biking - It's just a category, and every little subcategory is what it is. And like I said earlier, they all still have some things in common, but often we have nothing. A dirt jumper has very little in common with a cross-country marathon racer. The way they dress, the way the bikes, where they ride, how they train, what they eat…so there are very big differences, and that's what the sport has become. So there's something for everybody out there who wants to and not everybody is into every single subculture.

Daniel: I think sometimes people get a little bit caught up in “what” they are and what that identity is and, it's almost isolating, right? It's like, “No, I'm just a trail rider. I don't ride jumps or I'm just a dirt jumper. I don't ride cross-country; I don't climb.” It’s interesting.

Hans: Yeah. Yeah. There's one of each. Everybody's different. And that is a really beautiful thing about mountain biking - that there is space for individual interpretation still. Absolutely. You don't have that if you race BMX on a BMX track like everybody else; if you play soccer, you’re on a soccer field, and there's very little room for personal interpretation in terms of changing the rules or changing the way you're doing it. So that's with mountain bikes, we do have that to a degree.

It becomes really clear all of a sudden if you put a bike from 30 or 35 years ago next to the bike you're riding today, you go, “Wow, yeah, they still have two wheels and a handlebar.”

Daniel: Yeah, I think that's really amazing. We talk about how the sport has changed and everything else, but how have the advances in bikes influenced your riding over the years? How has all the technological growth and everything else changed what you ride, how you ride, and what you want to ride? How have you seen that evolve over the years?

Hans: Yeah, sometimes you wonder. It becomes really clear all of a sudden if you put a bike from 30 or 35 years ago next to the bike you're riding today, you go, “Wow, yeah, they still have two wheels and a handlebar.” But often it's the geometry and also the durability or stability of those bikes. I mean, we really rode pieces of crap back then, and they were flimsy little tires. I mean, there was a time you couldn't get a stem that was shorter than 120 millimeters. You couldn't find a tire wider than 2.1 or 2.2 at the best. You couldn't find a brake that actually worked because we had rim brakes or cantilever brakes. And even if they worked under a certain condition, they surely didn't work when there was all of a sudden water in the mix or some other element.

Everything on bikes would fail and break. There was also a lot of trial and error in terms of inventions. Some of them worked out and some of them have been long been forgotten, but often people jumped on those inventions, “Oh, that's the next cool thing.” And then, even within 12 months, they were like, how could we have been so stupid to ride those handlebars or elevated frames or whatever it was? And so there was a long journey, and bikes have come a long way and that makes a big difference. Then, also, a big, big part is where we ride and how we ride. The first 15 or 20 years of mountain biking, I think, was all about technology we just talked about. But then the last 20 years I think was more about where we ride and how we ride.

And it was about the trails because, in the old days, you would just ride whatever dirt road you could find, and those were often boring fire roads. And yeah, there were hiking trails and single track, and some hiking trails were way too extreme for the average riders while others were just nothing really exciting. And then, with the beginning of purpose-built trail, all of a sudden, some flow started to emerge from berms and from jumps and the whole bike park trail center culture. That really changed the most, and it also added way up the fun factor. All of a sudden, it was fun.

…but to really reach the masses…the fun factor is more important than the exercise payoff.

And with that, the bike parks that you don't necessarily have to pedal uphill because that held a lot of people back. And that of course has now been multiplied by the introduction of e-bikes, which also take the sting out of things and focus a bit more on why most people bike. I mean, I know some people bike to get the exercise. A lot of people bike for that reason and to get some pain, but to really reach the masses, I think the fun factor is more important than the exercise payoff.

Daniel: We see a lot of progress in trail development and advocacy…how important is trail advocacy to mountain biking right now?

Hans: It is so much more important than 99% of the mountain bikers realize it is. Organizations like IMBA have done so much valuable work. I mean, yeah, you can always pick and choose a few things that IMBA hasn't done or is not supporting. But overall, I mean all these people who are out there building trails now by themselves, be it legal or illegal, it came all out of the roots of IMBA and a few really distinguished trail builders who educated everybody else who came to these advocacy summits and told people how to build a trail sustainable and how to build a berm. A trail is not a trail and these really good trail builders are architects…they are artists. And they were really underappreciated for the longest time. For the longest time…when they finally realized that they might have to actually build something for bikers, then they thought it could be anybody who could swing a shovel could do that. But no, it's not sustainable, it's not fun, it's not predictable, it's not all those things that make a trail successful…

The group that is really for me right now is People For Bikes. They advocate for cycling altogether, including mountain bikes and e-bikes. They lobby in Washington, they build trail centers and pump tracks and bike lanes, and they educate legislators by trying to integrate bikers in the wilderness or e-bikes into the road system or build whatever. And it's so important and so good. That is one of the reasons why there's also such a bike boom: all this groundwork has been done by those organizations. Every biker has been affected by their work in one way or another, and they deserve support whenever it's applicable.

…as much as Rampage is the greatest biking event in the world maybe, and it is super cool to see the progression and all that, I think Red Bull really failed in educating the audience…

Daniel: Yeah, it's interesting, and important. I'm the president of our advocacy organization down here in western North Carolina, Pisgah Area SORBA, and we have a number of trail projects going on right now and a lot of people have been building non-system or illegal trails, and those trails are good. They're not built sustainably, but they're fun. But they brought in a bunch of law enforcement officers a few weeks ago and are shutting some of them down, and the organization's getting some blame for it, saying we had them do that or we should have advocated for these trails, which obviously can't be built and everything else you can imagine. None of it is true, of course. It's just interesting how people perceive trail advocacy when it's not exactly what they want it to be. However, there would be no relationship with the land managers, and the trails would just be closed for good, including all the trails, even the legal ones, if we didn’t advocate for them.

Hans: Well, the thing is, organizations like yours and IMBA always advocated in that way and told people to respect private land, don't build illegal stuff, build sustainability, all this stuff. But people wouldn't listen to them or wouldn't even read there. The message wouldn't reach these people, but the message that was reaching the people was the Red Bull Rampage. And I think as much as it is the greatest biking event in the world maybe, and it is super cool to see the progression and all that, I think Red Bull really failed in educating the audience about, “Hey, it's not okay to go out on any piece of land and start building stuff. It's private land, forest land, it's not sustainable, and so on...” And it opens up…and it is a really big problem. People think they can build anywhere now, and they really should not because it also closes doors, and there's a way to do it.

And yes, unfortunately, going the official route is also, it's a lot of red tape and it's a lot of headaches, and it's a lot of compromises that have to be made in the process-year-. But at the end of the day, we are not the only people out there enjoying nature. Unless you want to go buy your own 200 acres of land…and a lot of people have done that. Absolutely. That's where you can do that. But everything else is like, anyway, I think Red Bull could still do a better job in educating the viewers and this current generation, which is not just a certain age group, it's just the current viewership because they all go out, be it 12 year olds or be it 60-year-olds and build.

Daniel: I think one of the hard things for us is we have all these legacy trails that were here 30, 40, 50+ years ago before mountain bikes were a thing, and they're either hiking trails or they're just fire brakes where they ran a dozer through, and it's eroded, and it can be fun to ride. Sometimes, the Forest Service wants to close those down and then put new purpose-built trails in place, and people are upset that you don't have the rough, rugged, just blown-out trail anymore that's just dumping water and sediment into the trout streams. While we got rid of an eighth-of-a-mile trail and added three new miles of trail, they're complaining that “It's flowy. We don't want that.” It can't make everyone happy, as you said; it's a compromise.

I once heard the Eskimo had 12 different words for the word “snow” depending on its consistency. And that's why we needed just the name for this kind of trail.

Hans: It is, and you just have to get used to it. I always said when flow was the big thing 20 years ago and myself and this German trail-building guy, Diddie Schneider, who's one of the best ever out there, we came up with this term “flow country trail” and it was just a name for a certain kind of flow trail that was a trail that was never steep, never extreme and never dangerous. So, trails like that might've existed already in a few places. Most places were way more advanced. You had to be a pretty good rider if you didn't hit the backside of a jump, you didn't have enough speed for the next one kind of a thing. But the flow country trail didn't have that. And as I said, some places might've had a place like this, but nobody had a way how to articulate it or name this trail because our language wasn't defined enough.

Flow was flow. But if I tell you this trail was super flowy, you would have no idea there a 20 foot gap jump in there. So I once heard the Eskimo had 12 different words for the word “snow,” depending on its consistency. And that's why we needed just the name for this kind of trail. So if I tell you, Hey, come and ride with me on a flow country trail. (You know) oh, perfect, I can bring my little kids, or I can bring my hardtail or my enduro bike, or I could even get through on my gravel bike. And that was kind of the idea about it, to define our language and to build these things.

And when flow came, flow was a cool thing to experience, but at the beginning it was kind of exclusive because you had to be a good rider to reach the backslide on any jump on Dirt Merchant to have that stoke. But then the flow country trails, the cool thing was anybody could ride it and there were some B lines, and the good riders would just go twice the speed. It might've not been huge features, but they still were completely stoked at the bottom because there was so much cool flow factor in there that it worked for everybody.

We also saw that the biggest problem people in poverty face is mobility. If they don't have mobility, they don't have access to healthcare education or even work

Daniel: Let’s shift gears a little bit… I think that the way that many of us use bikes here in the United States or in any developed country is very different than how many people across the world use bikes. We use them for recreation primarily, but a lot of other people use bikes out of necessity. It's their transportation. It's how they get around. Tell us a little bit about Wheels4Life and what your organization does.

Hans: Wheels4Life does exactly that. It's a nonprofit charity that provides bikes to people in need of transportation in developing countries. I traveled to these (countries) on my adventure trips that I've done all over the world, often in really remote places. I was often the first guy ever with a bicycle in some mountain range or so on... We came across these villages and saw how people use the bikes completely differently. We also saw that the biggest problem people in poverty face is mobility. If they don't have mobility, they don't have access to healthcare, education, or even work because in their little village, there might not be work or healthcare, but 20 kilometers away, there is. Having a bike all of a sudden opens up all these possibilities for becoming an entrepreneur - to take your mangoes and sell them at the market 20 miles away or to go to school daily and not be late. People go to school far away, but they walk and then it takes up all their day and they're often late or they skip school. So anyway, we started this organization about 20 years ago. It’s a small organization; it's really my wife, Carmen, and I, and then we have a board, of course, and we have a lot of volunteers who have helped us over the years, but we've given away about 20,000 bikes now in those 20 years. But it's a very pure organization. We don't pay ourselves salaries or even travel expenses. We have no overhead, really; our office is here in this room.

So, we are just trying to set a good example, change a few lives, and inspire people to give back a little bit. Bike's been so good to me, and that's what we are doing with Wheels4Life.

Daniel: That's awesome. There are so many ways a bike can change a life, whether it's getting a kid in the neighborhood on one and them riding and ending up loving it or providing transportation to someone in a third-world country. What, do you have any stories of how you've seen it directly impact people? What's one of the more memorable things you remember throughout your life with this?

…the bike was the ticket for them to go to school, and they would finish secondary school, and they would go on to university. And literally, ten years later, they were now the doctors in their communities…

Hans: Well, there has been the one thing about being such a small organization like we are…we get a report from every bike we give away, and I could almost theoretically, I could give you 20,000 names of where those bikes have been. We are not just dumping a container somewhere in Africa and hoping the right people will get them… We have project leaders on site, and they send us reports. And some of these people, I mean in one of the places in Malawi in Africa, we started giving away ambulance bikes, which was basically a trailer that you could put behind the bike and somebody they could transport a patient on there. The very first time we delivered, it's usually a little ceremony at the village where the bikes were handed out to the hospital by our project leader, and it's a formal affair for them. They dress in their church clothes and come.

But that very day, there was a call that somebody was injured, and they literally saved a life by putting that ambulance on the bike, pedaling out there, and getting that patient to the doctor. There have other cases where for kids, the bike was the ticket for them to go to school, and they would finish secondary school, and they would go on to university. And literally, ten years later, they were now the doctors in their communities. And it was all because not only did the bike bring them to school, but whenever they weren't going to school they or a family member would also use the bike to go to the market and sell their charcoal or their mangoes, or they would use the bike for daily stuff, but the bike would often provide a form of income. So there have been some beautiful stories like that that really touch people, and it's hard to imagine because when you're in these remote villages, there is really no chance of getting out of there. The bike really opens up the doors for them to go beyond their village and have a hope for a better life. One guy I remember, we gave him a bike, and a few years later, we came by with a follow-up project, and then he showed us his house. Now, he had a tin roof on his mud, and he bought a cow. He had a sofa, a proper sofa in his mud yet, and even a TV, and he was able to buy all that stuff because he was able to become a construction worker and get work on a regular or semi-regular basis.

Daniel: So seeing bikes used like that, it's so different than what I think a lot of us are exposed to in our everyday lives, and it's a very different mindset of thinking of a bike as a means of transportation and a necessity and something that gets you from place to place, helping you literally live and do life, getting your water and getting to the store…than a means of recreation. If there was something surrounding all that that you wish people in our communities could take and internalize, knowing this, what would it be? It gives a lot of perspective to people arguing about some piece of tech in the comments on the internet when we’re talking about how bikes are just so important for many people’s lives.

If you are in the position to become a racer in some African or poor Asian country, you are in the upper class already. Because if you can think about getting a proper mountain bike and traveling to races…those people are not our target audience…

Hans: Well, like I said, we have to sometimes jump out of our own little bubble. Just like we said, there are all these subcultures in biking - dirt jumping and freeriders, and subcultures like the (internet) commenters, who have opinions. In some subjects, I often have very educated knowledge, and just reading those comments often shows how these people often have no clue what they're talking about. They just like to hear their own voice or make an argument that it's very one-sided, so you can only give that much importance to it. And unfortunately, in human nature, they listen to the squeaky wheel or cater to it. Somebody can have a hundred positive comments, but one guy said something stupid, as uneducated as it probably was, that still bugs them more than the hundred nice comments. But the overall message is yes, step out of our bubble. And that's what we did with Wheels for Life.

It is just as you said, bikes have a completely different meaning to these people, and it is transportation. It's not recreation. They cannot even understand, they don't even know what recreation is. They don't even know what a hobby is or a vacation, and those words don't really exist in their vocabulary. For them, it's more like survival, and traveling around the world has taught me that and shown me that. For example, we don't sponsor…I mean, as much as there are also cool programs that sponsor kids who want to become racers in those countries, if you are in the position to become a racer in some African or poor Asian country, you are in the upper class already. Because if you can think about getting a proper mountain bike and traveling to races…those people are not our target audience. There's nothing wrong with supporting these development teams in countries where racing is not big, but that's just not what we do at Wheels for Life. We really find the poorest of the poor and the ones that kind of get left out.

Daniel: So to start wrapping up, what bike are you riding right now? What’s your favorite bike?

Hans: My favorite bike is my e-bike. I've been pro-e-bikes long before it became a boom, but it came at the right time in my career, and I think they're really fun and cool, and they opened the doors to a lot more people to bring them to cycling. I still ride my analog bikes, too. I try to mix it up, but the hills here in Laguna are pretty steep.

And sometimes it's just more fun to go for a quick rip. I really like the new opportunities I have with the e-bike. I can ride stuff that I could have never done on an analog bike, and especially, I like these technical uphill trails, and I like to do some trials riding on the e-bike. And I'm not talking about hopping around, I'm talking more like old school riding over up and over stuff and super technical terrain. And so my GT eForce is a really cool bike and it also, it takes the whole adventure game on a whole different platform. Yes, there's a lot of logistics with batteries and recharges or bringing extra batteries, but that kind of also makes it fun and new and interesting. And I think that's part of the reason why I've been around so long. I am always trying to find ways to keep it fun and make it so I enjoy doing it. And the e-bikes kind of brought that back for me.

Daniel: One last question - What's the most exciting trend you see in the mountain bike industry now and where do you see things going? Where do you see yourself ten years from now?

Hans: Well, I think maybe the most exciting thing is kind of backs onto this earlier thing that I said about the infrastructure we see now for bikes all over the world pop up. And then you have places like Bentonville on the forefront, and they show us what's possible because they have deep enough pockets. But I think other places see that too. I think the next 20 years are going to be about building destinations. We're not talking about only where riders want to come visit and ride, but where riders want to live, where you build entire communities where you really don’t just feel tolerated, but it's all, it's like-minded people with like-minded stuff. And that can go in many different directions and every little subculture can have its little community or aspect of that.

I think that it’s cool when you go to some of these really neat developed resorts and towns that make you think, like, man, I want to actually live there. I don't want to just visit there. So I think that is one thing, and that all has a lot to do with these advocacy groups and it has to do with all the different subcultures, and the sport has just been evolving. We are here at the time where it's kind of nice to see. Yes, there are downsides with some trails getting busier than they used to be and things changing, but at the same time, there are so many more trails out there now that it still spreads out. It's not just like the three same trails that it often used to be.

Daniel: Do you feel like we're kind of at the pinnacle of things or do you feel like there's still a long way to go?

Hans: I think there will always be new ways to go in directions where we can't even imagine it. What's a bit scary is that things are moving more in the world than in cycling, but they're moving almost too fast right now with the whole AI thing. And even for these, part of my job is not just to ride bikes, but it's to create content for a lot of these professional riders, and now all of a sudden, you have these bloody AI-generated photos where I can do now 80-foot canyon gap, which I would've never come close to. With AI, I could create that photo, and it's a bit disturbing that now I start looking at photos on the internet and go like, “Yeah, but that's not real.” And you're not sure a hundred percent, but you're pretty sure that this was…it's just too perfect that whatever it is. Is it just a background or something? But that's a whole different issue…

Daniel: Well, Hans, man, thank you! This has been great. It’s also the first interview style piece we’ve done on this platform so we’re going to see how it goes. Any last thoughts from you?

Hans: Thank you, I’m honored to be that…I do think Danny MacAskill is worried that you and me are going to come up with a video soon that was AI generated that’s going to make him look bad.

Daniel: Hahaha, you never know…

To learn more about or to donate to Wheels4Life, visit wheels4life.org

Check out Hans’ YouTube channel here

Follow Hans on Instagram here

Hans is incredible. His knowledge and advocacy goes so much deeper than just mountain biking and trials. I’m glad you brought up how differently we view bicycles in the developed world, especially given our recent feature on the Buffalo Bicycle.

Having essentially pioneered the art of ‘earning a living as a non-racer’, the industry has finally adapted to what Hans was doing 30 years ago. Yet, he is using his reach for projects like Wheels4Life. Hans constantly reinvents himself and adapts to whatever bicycles are in the current moment, and that’s why he has remained so relevant for so long. Great interview.

This was a good read.

One thing that caught my eye is some of the Wheels4Life bikes have metal rods from the handlebars down to the front axles. I can't figure out what they would be for except a kind of suspension but I don't see any pivot points.

Also they seem to have front brakes actuated with a rod and a lever the full width of the handlebar. I never saw any like this before.

It might be interesting to look at this type similar to the Buffalo video, and raise more awareness for Wheels4Life. It seems like these might be Neelam bikes. They look maybe like the "Black Mamba" model but I can't find much info.